Ice Dams at Transitions: Roof-to-Wall Interfaces as the Primary Failure Zone

Introduction: Why Ice Dams Are a Transition Problem, Not a Roofing Problem

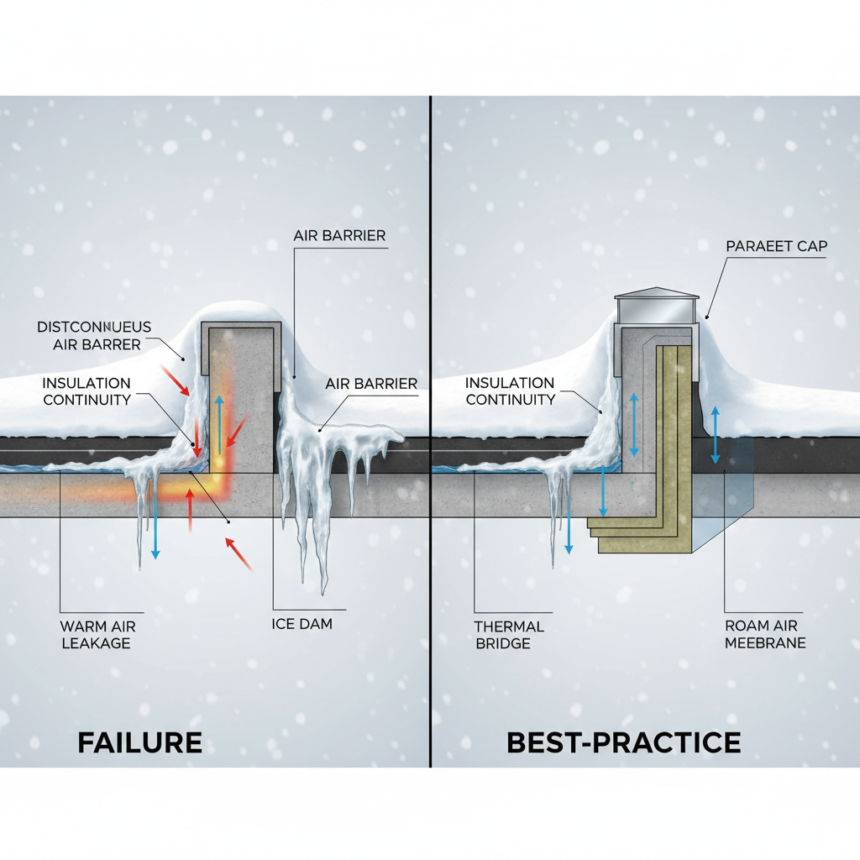

Ice dams are often framed as a roofing defect—an issue solved with more ventilation, thicker insulation, or heated gutters. In practice, the most persistent and damaging ice dams originate at roof-to-wall transitions, where air barrier continuity is interrupted and insulation geometry becomes compromised. These locations concentrate heat loss, create localized melt, and refreeze water at the coldest exterior edges. The result is a failure mechanism driven less by overall R-value and more by enclosure continuity.

This distinction matters because contemporary buildings increasingly rely on complex massing, parapets, and exterior insulation systems. Each adds surface area and transitions—exactly the conditions that elevate ice dam risk. For architects and enclosure specialists, ice dams are therefore best understood as a transition detailing problem with clear implications for durability, liability, and winter performance.

How Ice Dams Actually Form at Roof Edges and Parapets

At a basic level, ice dams form when heat escaping from the building melts snow on the roof, and that meltwater refreezes at colder exterior edges. The key question is not whether heat escapes—it always does—but where it escapes in a concentrated way.

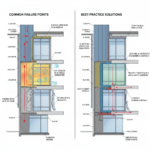

Roof-to-wall interfaces create ideal conditions for ice dam formation because they combine three factors:

- Discontinuous air barriers that allow convective heat loss

- Compromised insulation geometry that reduces effective R-value

- Cold exterior elements such as parapets, overhangs, and exposed slab edges

These conditions rarely occur uniformly across a roof field. They cluster at transitions.

At parapets, for example, interior heat migrates upward through the wall assembly and is often redirected horizontally at the roof line. If the air barrier turns the corner poorly—or not at all—warm interior air washes the roof deck locally. Snow melts at that location, flows toward the exterior edge, and refreezes against the cold parapet face or roof overhang. The ice dam grows incrementally, fed by repeated melt-refreeze cycles.

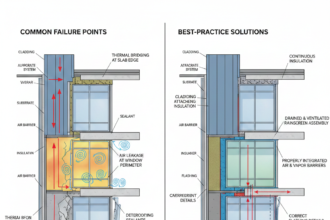

Air Barrier Continuity: The Primary Driver

Among all contributing factors, air leakage is the most potent. A small discontinuity in the air barrier can move orders of magnitude more heat than conduction through insulation. Roof-to-wall transitions are where air barriers most commonly fail.

Typical problem conditions include:

- Wall air barriers that terminate below the roof deck

- Roof air barriers that are assumed, not detailed

- Reliance on materials (such as batt insulation or gypsum board) that are not continuous or durable air control layers

- Unsealed interfaces between wall membranes and roof membranes

In many buildings, the roof air barrier is treated as a roofing scope issue, while the wall air barrier is treated as an enclosure scope issue. Without explicit coordination, the two never truly connect.

When warm, moist interior air leaks at these locations, it does more than melt snow. It can also condense within the assembly, compounding durability risk. Ice dams are often the visible symptom of a much deeper enclosure failure.

Insulation Geometry: Where R-Value Assumptions Break Down

Even when nominal insulation values appear adequate, roof-to-wall transitions frequently suffer from reduced effective R-value due to geometry.

Common conditions include:

- Tapered insulation that thins at parapets

- Structural framing interrupting insulation continuity

- Cantilevered slabs or roof edges with limited insulation depth

- Exterior insulation that stops short of the roof plane

At parapets, it is not uncommon to see exterior wall insulation terminate below the roof membrane, leaving the parapet cap and roof edge effectively uninsulated. Interior insulation may also be absent or compressed due to structure and anchorage requirements.

The result is a localized thermal bridge precisely where snow accumulation and cold exposure are greatest. These cold edges become the freezing point for meltwater generated upslope.

Parapets: The Highest-Risk Condition

Parapets deserve special attention because they combine multiple failure mechanisms.

From a thermal perspective, parapets are exposed on three sides and often lack sufficient insulation continuity. From an air control perspective, they require multiple direction changes in the air barrier—vertical wall to horizontal roof to vertical parapet face.

From a moisture perspective, parapets are routinely exposed to snow accumulation, freeze-thaw cycling, and water infiltration. When ice dams form against parapets, water is forced laterally into roof membranes, counterflashing, and wall assemblies.

In forensic investigations, parapet-adjacent leaks are frequently misdiagnosed as membrane failures. In reality, the membrane is reacting to hydrostatic pressure created by ice damming driven by heat loss at the transition.

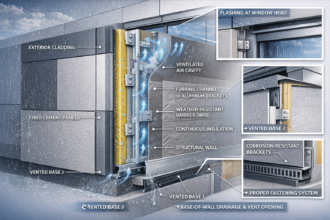

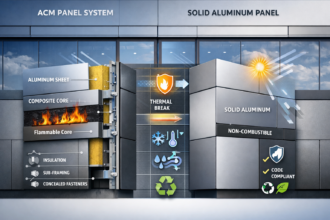

Exterior Insulation Systems and New Failure Modes

The increased use of exterior insulation and finish systems (EIFS), continuous mineral wool, and rigid insulation has improved overall thermal performance—but it has also introduced new transition risks.

Exterior insulation often stops at the roof line due to detailing complexity, fire separation requirements, or constructability constraints. If roof insulation does not extend over or align with wall insulation, a thermal and air barrier gap is created.

Similarly, roof membranes are sometimes installed before wall insulation, making later continuity difficult or impossible without rework. These sequencing issues are not theoretical; they are a common contributor to ice dam problems in otherwise high-performance buildings.

Why Complex Massing Makes Ice Dams More Likely

Modern architecture favors articulation: step-backs, terraces, overhangs, and multiple roof elevations. Each introduces additional roof-to-wall transitions.

Every transition is a potential failure zone. As massing complexity increases, so does the probability that at least one transition will be poorly detailed, poorly executed, or both.

From a risk perspective, a single weak transition can dominate winter performance. Ice dams do not require widespread heat loss—only enough localized melting to initiate the cycle.

Common Design and Construction Mistakes

Several recurring issues appear across projects and climate zones:

- Assuming roof ventilation solves ice dams without addressing air leakage

- Relying on interior insulation at parapets with no exterior thermal continuity

- Failing to detail air barrier turns at roof-to-wall interfaces

- Delegating transition detailing to submittals rather than construction documents

- Ignoring sequencing constraints that make continuity impractical in the field

These mistakes are rarely the result of ignorance. More often, they stem from fragmented responsibility between disciplines and trades.

Practical Strategies for Reducing Ice Dam Risk at Transitions

Effective mitigation focuses on continuity, not components.

Key strategies include:

- Explicitly detailing air barrier continuity from wall to roof to parapet

- Aligning insulation planes so wall and roof insulation overlap or interlock

- Providing sufficient insulation at parapets, including exterior insulation where feasible

- Coordinating sequencing so continuity can be executed as designed

- Using mockups and inspections to verify transition performance before enclosure close-in

In cold climates, these strategies should be treated as baseline requirements, not premium upgrades.

Why This Matters for Architects and Enclosure Specialists

Ice dams are not merely a maintenance issue. They drive warranty claims, interior damage, and long-term deterioration of roof and wall assemblies. More importantly, they expose weaknesses in enclosure design that can have year-round consequences.

As buildings become more energy efficient and more geometrically complex, transition performance becomes the controlling factor. Roof-to-wall interfaces are where design intent meets construction reality.

For architects and enclosure specialists, addressing ice dams means owning the transitions—thermally, airtight, and constructively. When those transitions are resolved, ice dams become far less likely, even in severe winter conditions.

Conclusion

Ice dams disproportionately originate at roof-to-wall transitions because these locations concentrate air leakage, thermal bridging, and cold exposure. Parapets, in particular, represent the highest-risk condition due to their geometry and detailing demands.

Understanding why ice dams form at roof edges and parapets shifts the solution away from superficial fixes and toward fundamental enclosure continuity. In an era of complex massing and exterior insulation systems, that shift is not optional—it is essential for durable, high-performance buildings.