**Fire, Facades, and the Post-IBC Landscape:

Are We Designing to the Code—or to the Risk?**

Introduction: The Disconnect Between Compliance and Resilience

In the last decade, the building industry has witnessed a striking paradox: despite increasingly rigorous fire safety regulations embedded in the International Building Code (IBC) and its referenced standards, combustible cladding failures persist in high-profile fires around the world. Whether triggered by ignition sources at grade, balcony fires, or interior-to-exterior flame propagation, these events reveal that meeting prescriptive code criteria does not always translate into meaningful resilience on a completed facade. In a landscape where insurers are tightening terms and owners are demanding reduced risk, the facade engineer and architect must ask: Are we designing to the code — or to the risk?

This article examines the limitations of current IBC facade fire provisions, explores why compliance alone is insufficient for real-world performance, and evaluates the impacts on material selection and assembly design strategies.

Understanding the Post-IBC Regulatory Framework

In the past two IBC cycles, facade-related fire provisions have expanded in scope and complexity. Key elements now include:

- NFPA 285 compliance for combustible exterior wall assemblies on many building types.

- Limits on combustible materials based on building height, occupancy, and proximity to property lines.

- Clarified requirements for fire separation distances and vertical/horizontal fire barriers.

These provisions are intended to mitigate exterior flame spread and assembly involvement during a fire. However, the structure of the code — predominantly performance-based for fire resistance and prescriptive for material use — means that compliance is frequently proven through discrete tests rather than holistic system performance.

Why this matters: Most codes focus on what gets tested rather than how assemblies behave in real dynamic environments. The result is a regulatory landscape where pass/fail criteria can mask critical vulnerabilities rooted in design intent, detailing, installation quality, and service conditions.

The Limits of Facade Fire Testing Standards

NFPA 285: Necessary but Not Sufficient

NFPA 285 has become the de facto performance test for combustible exterior wall assemblies referenced by the IBC. It was developed to assess flame propagation through an assembly under controlled exposure conditions. While NFPA 285 provides valuable data on relative fire performance among assemblies, it has limitations that affect real-world applicability:

- Single Test Protocol: NFPA 285 evaluates a specific wall build-up under a defined heat and flame exposure. It does not simulate:

- Variable field conditions (wind, rain, thermal gradients).

- Complex interfaces (windows, protrusions, penetrations).

- Aging and environmental degradation.

- Detail Sensitivity: Minor deviations in cladding support, insulation continuity, or joint geometry can dramatically alter performance in actual fires, yet NFPA 285 only validates one tested configuration. Unqualified substitutions or on-site variations may render the tested result invalid for the installed condition.

- Ignition Source Variance: Real fires often begin external to the envelope (e.g., balcony grills, adjacent combustibles). NFPA 285 does not replicate external ignition scenarios causing lateral spread across cladding surfaces.

As a result, designers may select materials that are “compliant” under NFPA 285 yet assembled in ways that are vulnerable in real events.

ASTM E84 and Material Classification

The ASTM E84 “Surface Burning Characteristics” test is widely used to classify materials as Class A, B, or C. However:

- It evaluates material surface performance in isolation, not as part of a complete wall system.

- Many facade materials achieve favorable classifications through treatment or coatings that degrade over time.

- E84 does not address concealed combustibles behind the surface — typically where fire propagation is most damaging.

Thus, the E84 classification can provide a false sense of security when used as a primary selection criterion.

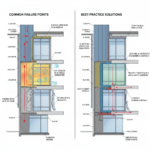

Case Studies: When Compliance Didn’t Protect Against Risk

Several widely reported incidents illustrate how compliant design solutions fell short in practice:

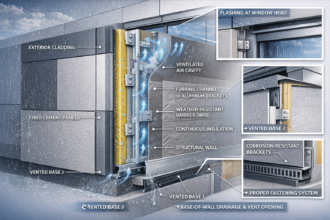

- Exterior Cladding Fires: Buildings with combustible rainscreen facades met NFPA 285 requirements yet experienced rapid fire spread due to unprotected cavities, poor barrier continuity, or ignition at recessed balconies.

- Siding Ignition at Base: Class-A rated siding installed above combustible foam insulation performed poorly when lower-level debris ignited between the cladding and insulation, demonstrating that E84 rating alone cannot predict systemic behavior.

In these cases, the assemblies were code-compliant on paper but lacked critical resilience features that govern fire behavior in real scenarios. The lesson for facade engineers and architects is clear: performance in the field depends on integrated system behavior rather than isolated component ratings.

Designing for Resilience: Beyond Minimum Code Compliance

1. Prioritize Systematic Fire Path Analysis

Treat the facade as a holistic system with multiple potential fire paths:

- Vertical and horizontal cavities

- Thermal insulation continuity

- Fenestration transitions

- Penetrations and interfaces

Use computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling and compartmental fire modeling early in design to understand how flames and hot gases might propagate through assemblies. This step goes beyond code checklists to uncover hidden vulnerabilities.

2. Specify Fire Barriers and Cavity Firestopping Thoughtfully

The IBC and referenced standards allow fire barriers and firestops as strategies to segment combustible cavities. However, their effectiveness depends on:

- Continuity across floors and around opening perimeters

- Compatibility with adjacent materials

- Installation quality and inspection

Detailing firestops around penetrations, at slab edges, and at compartment lines should be treated as integral to performance, not optional add-on tasks.

3. Material Selection with Real-World Performance in Mind

When selecting facade materials and insulation systems, consider:

- Aging and environmental effects: How will mechanical fasteners, winds, UV exposure, and humidity affect combustible components over time?

- Moisture interactions: Water intrusion can compromise fire barrier materials and adhesive bonds, altering fire performance.

- Substitution risk: Know which materials are qualified by the fire test and which are field substitutes — limit the latter.

In practice, this means favoring assemblies with inherent fire resistance rather than reliance on nominally compliant but marginal configurations.

4. Coordination with Life Safety and Egress Strategies

Facade fire performance does not exist in isolation. Fire spread across an exterior wall can compromise occupant egress, fire department access, and compartmentation strategies. Work closely with life-safety consultants to ensure that exterior performance supports overall building fire strategy.

Insurance, Owners, and the Business Case for Resilience

Increasingly, insurers are scrutinizing facade combustibility and fire protection strategies when underwriting policies. In some markets, buildings with higher combustible content or unprotected cavities face:

- Higher premiums

- Exclusions for facade fire damage

- Requirements for additional mitigation or third-party assessments

Owners, too, are more attuned to risk exposure. A significant fire can mean:

- Hours of business interruption

- Reduced asset valuation

- Reputational damage

- Communities questioning safety practices

For facade engineers and architects, this convergence of regulatory, financial, and reputational pressures means that designing “just to code” exposes clients to downstream risk.

Material Selection in the Post-IBC Landscape

In light of the above, material selection becomes not merely a compliance exercise but a risk management strategy.

What to Evaluate in Material Selection

- Intrinsic Fire Performance: Assess combustibility and reaction-to-fire characteristics over service life, not just initial classification.

- Assembly Sensitivity: Some materials perform well in nominal conditions but are highly sensitive to detailing or tolerances (e.g., fiber-reinforced polymers near joints).

- Compatibility with Fire Barriers: Ensure materials don’t undermine adjacent fire protection (e.g., through melting, off-gassing, or poor adhesion).

- Installation and Quality Assurance Risk: Specify materials that reduce complexity and minimize field variability.

Practical Selection Strategies

- Favor non-combustible insulation and sheathing in high-risk applications when feasible.

- If combustible materials are used, incorporate engineered fire barriers with tested interface design.

- Reject materials that show disproportionate degradation under moisture cycling or UV exposure without protective design.

By integrating fire performance as a core selection criterion — not an afterthought — designers align material choices with real risk profiles.

Common Mistakes and Misconceptions

Mistake: Equating E84 Classification with System Safety

The surface burning characteristics classification is a useful data point but insufficient as a proxy for assembly fire behavior.

Mistake: Treating Fire Barriers as “Check-the-Box” Items

Incomplete or poorly detailed fire barriers undermine the purpose of code requirements. Prioritize continuity and inspectability.

Mistake: Assuming Tested and Installed Assemblies Are Equivalent

A test report applies strictly to the assembly tested. Unapproved substitutions, altered joint details, or unanticipated penetrations invalidate that report’s applicability.

Misconception: Code Compliance Ensures Insurability

Insurers often evaluate risk beyond minimum compliance. Compliance does not guarantee favorable terms; resilience does.

Conclusion: Designing for Risk, Not Just Compliance

The post-IBC facade fire landscape challenges conventional assumptions about safety and performance. As codes evolve, so too must the mindset of facade engineers and architects. Compliance — while essential — is a baseline. True resilience arises from a rigorous understanding of:

- System fire dynamics

- Material behavior over time

- Integration of barriers and interfaces

- The broader risk landscape

In an era of heightened scrutiny and liability, professionals who design beyond compliance will deliver not just safe buildings on paper, but resilient facades in reality.